Aristotle’s idea that everything in the universe was made up of four principal elements – fire, water, earth and air held a great deal of weight until atomism was proposed. It became obvious to almost everyone, let alone scientists, that the world was made up of several “elements” and not just the ones proposed by Aristotle. By the late 18th century, chemists had identified, isolated and studied some of them. Notably, they realized that certain elements always reacted in a typical fashion in the same proportion.

Early Classifications of Elements

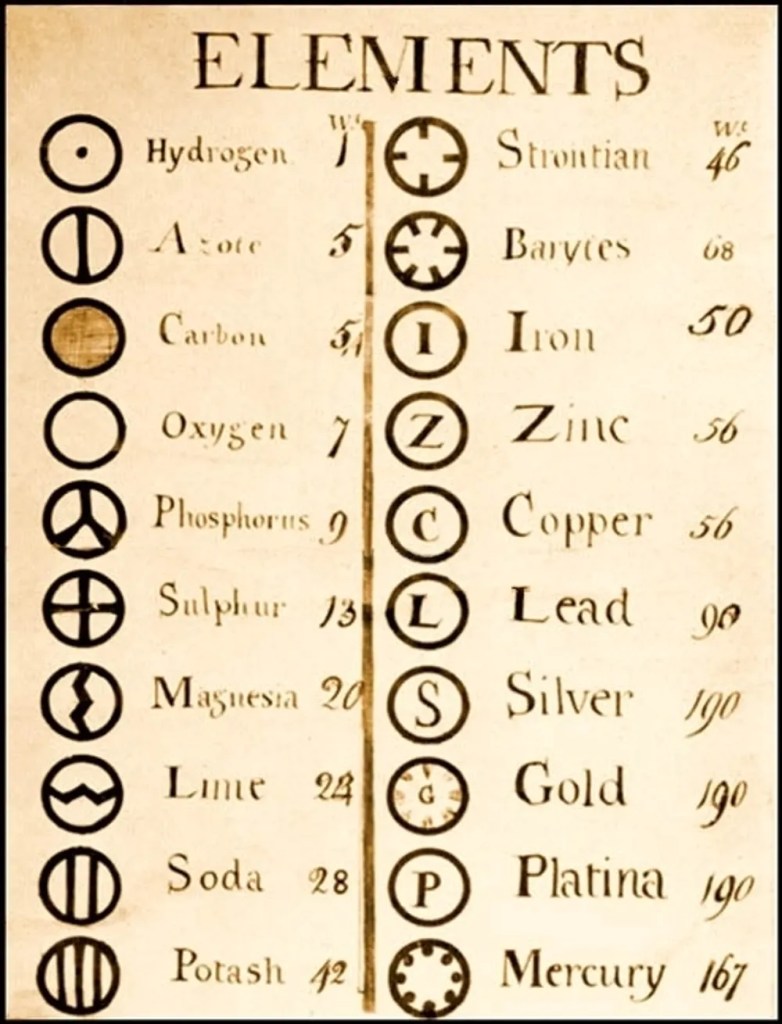

It was John Dalton, an English scientist who proposed the atomic theory in 1803. Matter was composed of indivisible, indestructible building blocks called atoms according to his theory. Further, Dalton reasoned that all atoms of one single element would be uniform in their properties, while atoms from different elements would be different. Dalton created a table listing some important elements with rather interesting symbols (see figure below). Armed with this new and exciting knowledge, other chemists embarked on a quest to study elements. When patterns were seen in the behaviour of some elements, chemists segregated them based on their atomic masses. Johan Dobereiner grouped certain elements in threes by their atomic masses and observed that the middle element had an atomic mass that was the average of the other two (eg. lithium, 7; sodium, 23; potassium, 39). This classification was known as the triads. However, not all elements could be classified into such triads. John Newlands proposed the law of the octaves, where every eighth element was similar to the first. Remarkably, Newlands based his idea on the seven notes in music, and while there were indeed a few similarities between the elements, not many accepted his arbitrary classification based on musical notes. Chemists had still not found an acceptable way to classify elements.

Enter Mendeleev

Meanwhile in Russia in 1869, Dmitri Mendeleev was developing his own set of ideas on chemical classification. At that time, elements were classified as either metals or non-metals based on their valency (the ability to react with other elements). Mendeleev was not entirely satisfied with this classification, and tried to group elements in such a way that could draw out their relationships. His classification was based on similarity of properties, but the brilliance of Mendeleev lay in the fact that he left several blanks in his classification to account for elements that were yet undiscovered. Even more presciently, he accurately predicted the properties of some of the elements that would later go on to fill up those blanks. Until that point, chemists were busy fiddling with element classifications based on elements that were already known; Mendeleev’s insight lead him to leave out gaps in his table for the unknown.

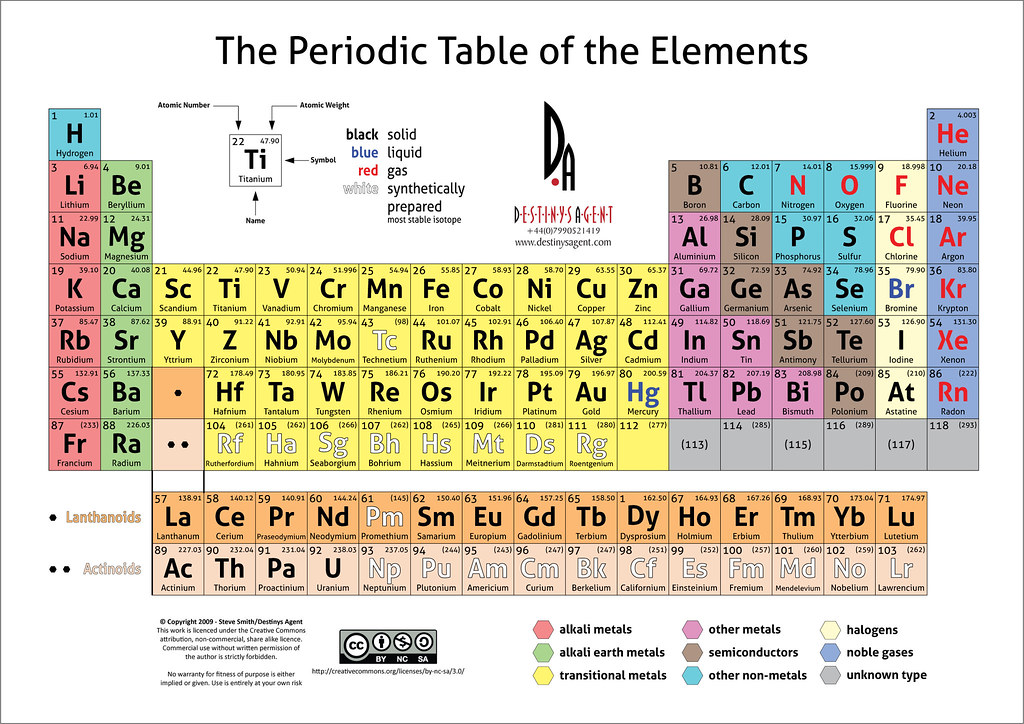

An important feature of Mendeleev’s classification was that he classified elements based on chemical features, which clashed with their positioning via atomic mass. In the above table, you will observe that tellurium with an atomic mass of 128 comes before iodine (atomic mass 127). Another striking feature of Mendeleev’s classification was the question marks he left. These question marks denote the elements that were not yet known in Mendeleev’s time. Adjacent to aluminium where Mendeleev placed a question mark, he accurately predicted an element with a mass of 68 and a very low melting point. Sure enough, when gallium was discovered, it slotted in perfectly with the same properties, vindicating Mendeleev’s classification. Mendeleev also predicted the properties for scandium, germanium and technetium much before they were discovered.

As newer elements were discovered that fitted seamlessly with Mendeleev’s observations, the confidence of the scientific community in his classification increased. This classification was after all, the first one that actually predicted the existence of newer elements. This not only spurred chemists to discover new elements, but also made it easier to study their chemistry and predict what type of compounds might be expected from them. However, despite his brilliant classification, Mendeleev was still vexed with a few problems. He could not figure out what do with a series of 15 elements, termed lanthanides. Though they were similar to each other, they did not fit well with the rest of the table. Not finding a suitable answer, he just pushed them down to the bottom of the table. Today, they still occupy the same place in the modern periodic table! Other problems related to radioactivity and isotopes (different forms of the same element with different mass numbers). Radioactive elements disintegrated and led to formation of newer elements, while isotopes seemed capable of occupying different positions in the table simultaneously. The advancement in quantum theory and discovery of the atomic nucleus solved these problems. With Moseley’s discovery of the atomic number, it made much more sense to classify them using atomic numbers instead of using atomic mass. Isotopes could now occupy a single place in the table, while radioactive elements too could be classified effortlessly.

The Modern Periodic Table

Today, a periodic table is elegantly displayed in just about every chemistry lab. Rightly, Mendeleev is considered as the “father of the periodic table” for his insightful contributions on element classifications. The modern periodic table is very much based on Mendeleev’s early classification, though it is oriented differently with the addition of several rows and columns. The rows in the periodic table are known as “periods”, while the columns are called “groups”. There are 18 groups and 7 periods in the modern periodic table.

The periodic table as we know it today is managed by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry, or IUPAC (eye-you-pack). Elements with high atomic numbers (above 100) can also fit nicely in this table, and there is room for newer elements as well (though most of the new elements are synthesized artificially). Though there are all sorts of versions of the periodic table (circular, long, spiral, 3D versions etc), the official version is still the one based on Mendeleev’s classification.

Moving forward

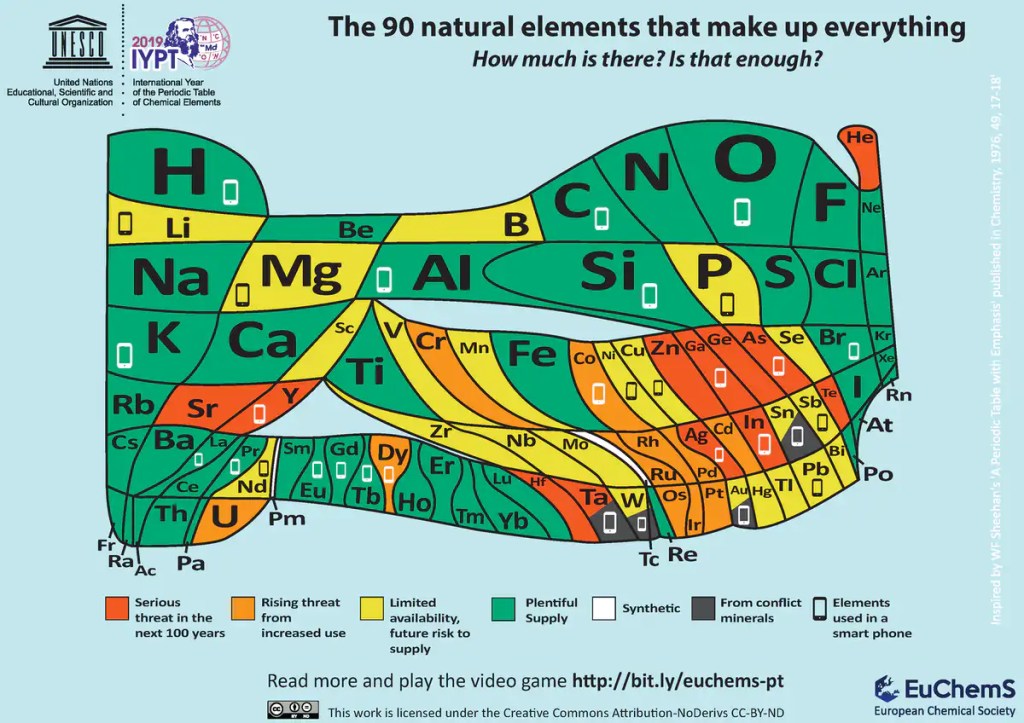

Though the current version is unlikely to be changed officially, new attempts have been made to improve the classification. One of the latest attempts was proposed by scientists Zahed Allahyari and Artem Oganov, published recently in the Journal of Physical Chemistry. They propose that elements be assigned what is known as a “Mendeleev Number”, which is derived from the most important atomic properties like atomic radius, valency, electronegativity (how strongly an atom attracts electrons to itself) etc. This new classification can enable construction of a grid of binary compounds (compounds made up of two elements, such as common salt, NaCl). It can also predict the properties of new compounds that aren’t into existence currently, which will be useful for new technologies in the future. One such classification is given in the figure below. Though it appears confusing, it gives useful information about the importance and abundance of elements. Naturally abundant elements are shown in bigger text boxes at the top, while scarce elements occupy smaller boxes below. Elements used in mobile phones contain a mobile symbol. Several elements that are essential for useful technologies are becoming scarce today. A classification by this new approach can provide insights into replacement materials obtained by a study of Mendeleev Numbers.

The charm of the periodic table isn’t lost even after 150 years (2019 was officially declared as the “International Year of the Periodic Table”). It is not just a fascinating educational tool, but also useful for chemists in their quest for newer materials.

One thought on “An Elementary Affair: The Story of the Periodic Table”