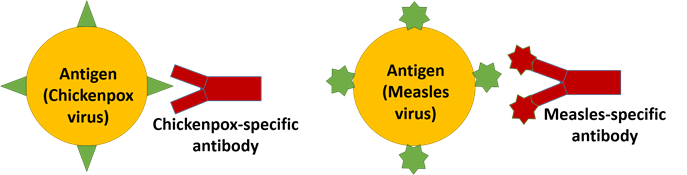

When disease-causing germs enter the body (which acts as a “host” to the germs), the immune system of the host launches a defence to destroy the germs and protect the host from the disease. In immunology, the invading germs, which can be bacteria, viruses, parasites or fungi are known as antigens. An antigen is thus any foreign substance that enables the host to produce an immune response (sometimes even pollen and certain chemicals trigger an immune response in some individuals, leading to pollen allergy). When an antigen enters the host, the immune system of the host responds by producing antibodies to neutralize the antigens. The antibodies are proteins that bind to the antigens and destroy them. It is important to note that the antibodies have a specific shape that allows them to bind to a certain type of antigen. This is similar to a lock and key, where a lock can be opened only by one type of key. Similarly, antibodies for a specific antigen may not be able to bind to other antigens causing a different disease.

Every antigen has a specific antibody that can bind to it. When a new antigen enters the body, specific antibodies need to be made by the host’s immune system.

Apart from antibodies, the immune system also activates certain cells called as “memory cells”. These memory cells remain alive even after the antigen has been eliminated. The memory cells contain instructions to generate antibodies against the antigen. In case the same antigen enters the body again, the memory cells immediately generate a large number of antibodies, and the disease never occurs. This is the reason why certain diseases like chickenpox only occur once.

Vaccines

So what is a vaccine and how does it confer protection? A vaccine is a kind of medicine that specifically trains the immune system to recognize a specific disease-causing antigen and neutralize it. Vaccines either contain an inactivated antigen (a dead bacterium or an inactivated virus) or part of the antigen (a specific protein from the virus or bacterium). These inactive antigens do not cause the disease itself, but elicit an immune response from our bodies and build up antibodies and memory cells. When the actual pathogen later enters the body, the immune system is already primed to produce antibodies and kill the pathogen, and no disease occurs. Vaccines thus protect people from diseases without having to get the disease at all (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-muIoWofsCE).

Essential Points about Vaccines

- It takes around two weeks for the body to produce sufficient antibodies after vaccination. In case a vaccine requires two doses, the antibodies need at least two weeks after the second dose to build up. If in the meantime, you are exposed to the antigen, you may risk getting an infection. That is why, you should follow safe practices even after getting a vaccine and not be careless.

- Symptoms of fever, weakness and soreness after vaccination means that your immune system is actually building up a strong defence against the disease. It doesn’t mean that the vaccine has failed. Quite the contrary.

- Sometimes, viruses alter themselves by acquiring mutations. If the mutations are relatively insignificant, it does not have an effect on the efficacy of vaccines. However, if the mutations significantly change the form and structure of the viral antigens, the efficacy of existing vaccines comes down and a new vaccine needs to be made. That is why, mutant strains are monitored closely during a pandemic.

- It requires an enormous amount of planning and research to come up with vaccines. Extensive trials are conducted, and safety and efficacy of the vaccine are thoroughly considered before approving it for public use. It is thus safe to take vaccines.

What are the different types of (COVID) vaccines?

The main types of vaccines (COVID vaccines, but these are also applicable for other diseases) are mRNA vaccines, protein subunit vaccines and vector vaccines. Each of these vaccines has a slightly different mode of operation. mRNA vaccines contain genetic material from the virus that makes a harmless viral protein in our body. The immune system then builds up antibodies against this viral protein and destroys it. When the actual virus enters the body, there is sufficient accumulation of antibodies to kill the virus. Protein subunit vaccines contain a protein from the surface of the virus that is injected into the body. This protein triggers antibody generation against the virus. Vector vaccines contain a vector that carries inactivated material from the virus. The vector thus acts as a vehicle to deliver the inactivated viral material. The body responds the inactivated viral material and generates an immune response.

Vaccination has an interesting history

Previously, it was discovered that certain individuals who had contracted smallpox and were cured never got the disease again. This discovery sparked off further thought and research into developing vaccines. In 1796, Edward Jenner, an English doctor, successfully developed a method to treat smallpox. He theorised that milkmaids who got cowpox, a mild form of smallpox, could be protected against smallpox. To test this theory, he collected material from a cowpox sore from his maid Sarah Nelmes’ hand and inoculated it into the arm of James Phipps, a 9-year-old boy. When James was later exposed to smallpox virus, he survived and did not develop the disease. Jenner published his work “On the Origin of the Vaccine Inoculation” as a treatise and hoped for annihilation of smallpox, which was a killer disease with very high mortality. Edward Jenner is considered as the “father of vaccines”, though he wasn’t the first to suggest a remedy for developing vaccines. Later, Louis Pasteur’s efforts spearheaded the development of a vaccine for cholera. Gradually over the next century, enough scientific knowledge accumulated and it became possible to develop freeze-dried vaccines on a large scale. Vaccines were developed to protect people from pertussis (1914), diphtheria (1926), tetanus (1938) and poliovirus (1955). With immense coordinated efforts, vaccination was taken up on a large scale in many countries, and several life-threatening diseases have since been eradicated or controlled significantly. Today, with significant advancements in molecular biology, better vaccine delivery systems, more effective vaccines for major diseases and therapeutic vaccines for autoimmune disorders, allergies and addictions are being developed.